Why learning from digital texts is still a challenge?

Ebooks have been around since late 70s with Project Gutenberg, and became a commercially available format as early as the internet enabled monetary exchanges in the 90s. In 1998, US libraries were already distributing free ebooks through their websites and technologies from companies like OverDrive have been supporting that effort since the late 80s. Fast forward to the 2000s, Amazon and Apple brought digital to the masses with simpler ereaders and smarter phones. Yet, this move has been really slow. I mean it isn’t a Kodak moment: print books are still popular, and digital versions are their less-flexible equivalents.

We’ve temporarily enjoyed the weightlessness option: we bring all the books we want and can with us, everywhere, and we don’t carry all those backpacks with heavy textbooks that break our backs. But this isn’t enough to make us read always on our devices. Print books aren’t vintage, they are still very much a preferred option 40 years after the first books went electronic. When digital photography came about, it made it easy for anyone to become an artist, flattening the requirement to enter the field. Digital books haven’t yet delivered an impact of this scale.

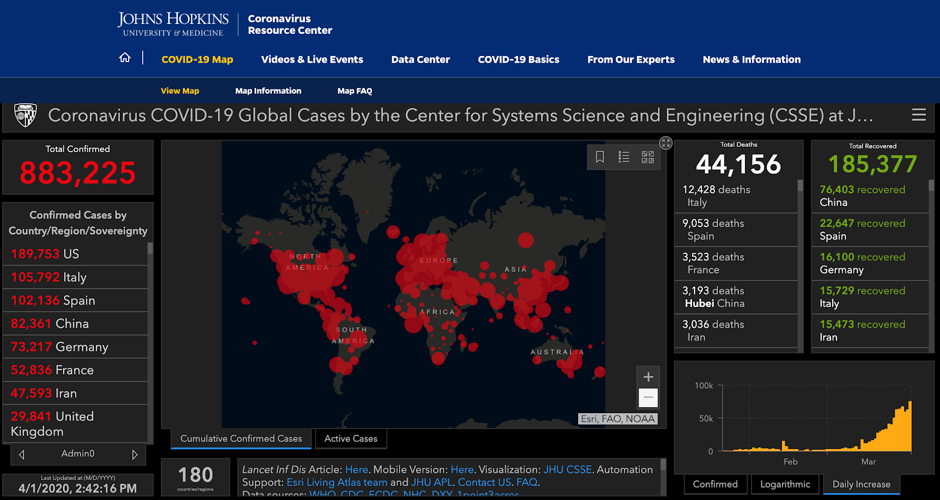

Arguably, lower pricing and instant access are a bonus. And that helped in 2020. Tax incentives (in the UK for example) and the limitations on physical due to the pandemic boosted the digital books market, while print sales declines more than in previous years with shops closed. 2020 was especially catalytic for etextbooks. The working and studying from home engendered an almost prescribed growth in digital textbook sales, which is unlikely to be sustained, because learning by reading digitally continues to be a frustrating experience.

All you can read

We expect the price of digital books to be lower than print, given the absence of a physical product, which is achievable and has little impact on the underlying business model. We purchase for our Kindle or Kobo, via Hive, or even a publisher direct to consumer (D2C) subscription like that of O’Reilly. We share it with family and friends, and it’s quite like what we’d do with a print book. The author can still get royalties (approximately) associated with one sale.

With textbooks, affordability has been a core value proposition of all the new technologies aggregating them, and they have succeeded. Renting textbooks went mainstream in 2008; according to the National Association of College Stores, the student spending on textbooks and course materials decreased from ~$700 on average in 2008 US and Canada to ~$400 in 2020.

Digital library alternatives, that offer access to at least half a million books and textbooks for under $20 a month like Perlego (2016), and sometimes let you publish and sell your own like Scribd (2007), are forcing the publishing industry to rethink author royalties. While they simplify and integrate the reader’s experience, charging the price of a book or less per month, they merely replicate physical reading and have done little to transform it.

A similar push to disrupt the author royalty model comes from B2B digital library subscriptions, like BibliU (2015) and Kortext (2013). Given the buyer is the institution, and the bundle price is driven by their size, the price per book gets into the exotic derivatives market. A library purchase can get a digital copy of the textbook that, unlike your Kindle, can be used by multiple students at the same time.

An intro textbook in Calculus, for example, would be used across all STEM majors by at least half of all the first year students, so just over one thousand at a mid-size university, who can all borrow the digital copy via BibliU or Kortext. The cover price is an important incentive for the author. Writing a textbook is a far more complex and time-consuming project than a non-fiction book or any other piece of writing that academics are accustomed to doing, argues the American psychologist Robert J. Sternberg. To make an all-inclusive textbook subscription model successful, the author’s compensation must go through some form of creative destruction (assuming print is off the table), unless the price of an etextbook purchased by an institution is allowed to vary depending on an estimated number of users that will borrow it (which isn’t working very well right now).

Digital apps from OverDrive are adding to this conundrum within the book (as opposed to textbooks) library renting experience sending the idea of late fees into oblivion. The company reports that their users borrowed “430 million ebooks, audiobooks and digital magazines in the past 12 months [2020], a 33% increase over 2019”, while more than 20 thousand new libraries and schools signed up.

With $200M raised among them, these technologies made strides with affordability. They even tried to improve and personalize your reading experience, with functionality that ranges from changing the font and background, to highlighting the text, adding notes, text-to-speech, bookmarking, dictionaries, chapter summaries and other neat elements. These affordances replicate those of physical reading, sometimes even delighting the user with instant word searches. It works quite well when reading for pleasure; when learning, however, our brain collects information spatially. We tend to remember really well where fragments of information are located on the page and what that page looks like. We lose that ability when we read on Kortext or Perlego, and even more so with all the apps that train you to read for speed, like Spritz and Spreeder.

Second generation enhancements

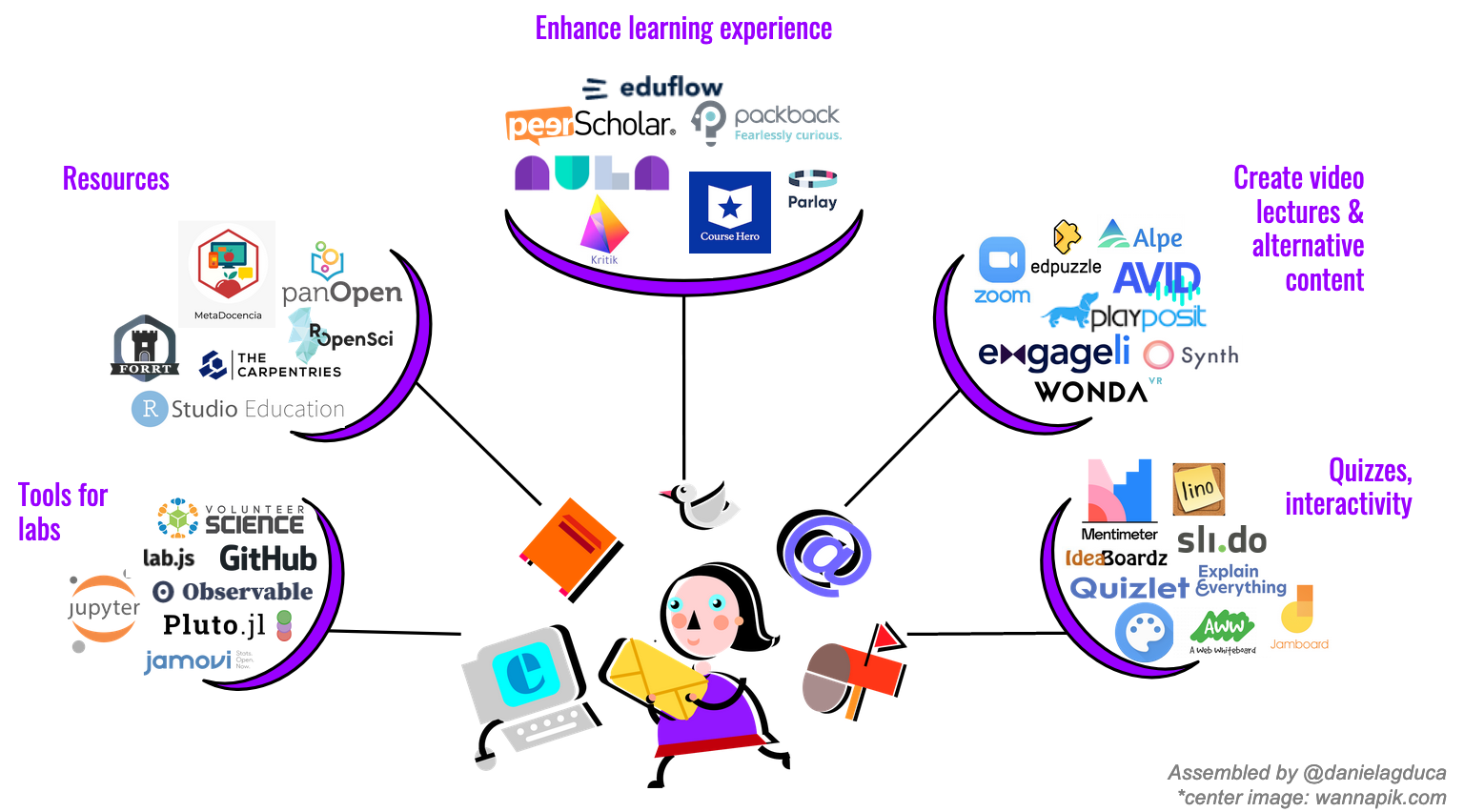

In 2015, after 4 years of research on how college students learn with and from textbooks, a group of academics at Harvard developed perusall. Perusall isn’t addressing affordability, but rather improving the effectiveness of student reading; the application focused on the job-to-be-done: learning. And it enabled learning from book chapters, articles and other materials, through social interactivity and adding the lecturer back into the process. In other words, students can share notes and highlights, start discussions on the margin, answer each other’s questions about the material, and the instructor has all this data to help them decide when to engage.

Glose has been taking social reading to the mainstream in France and Europe since 2014; and was just acquired by Medium - the content publishing platform, an indication that social reading is already an expected feature of any reading interface. The apps fixing the affordability challenges (BibliU, Kortext, scribd, perlego, clasoos) also offer social reading functionalities. The approach to social reading that fires me up even more, in fact, is that of reading.supply. While it doesn’t contain/support books and textbooks, it does a much better job at helping you develop your knowledge while socially reading with the very neat option of manually building graphs of knowledge.

Independent and group notetaking while reading online is neither new nor unusual. With all the content on the internet, bookmarking and annotation evolved quite organically. diigo (2005), hypothes.is (2011), and memex (2015) are just a few of the tools that enable this functionality and are popular with universities. Memex builds on the idea that we learn from reading if we can build a knowledge graph, and tries to support the user in organizing the information from bookmarks and online annotation in that form. This isn’t something that I’ve seen in any of the digital textbook applications.

Can you read it all and learn from it?

While notetaking has been linked with improved learning outcomes both in print and digital, there are very few studies that test its benefits for college students, and even less that look at digital course text. These suggest that guided notes, along with self-questioning and immediate summaries have the strongest and most consisten effect on student learning. Furthermore, we know that learning happens as a result of spaced repetition, breaking down the content, returning to previous chapters to review and flipping through the pages of later chapters to inquire.

These affordances are slowly being picked up by reading technologies. Readwise tried to crack spaced repetition for the kindle readers. Mindstone launched in February 2021 promises features that are based entirely on the science of learning. It organizes your reading and notes, compounds them into a knowledge graph, and lets you set up reminders to support spaced repetition.

Retention and comprehension can also be achieved with associated visual cues (like pictures and videos) in multiple media formats especially when reading in a second language. Several textbook aggregator apps are adding materials to their platforms, but that is not yet as integral a part of the main reading experience.

Erudite doesn’t yet support textbooks, but it’s transforming the reading experience for college students. Powered by several algorithms, the app breaks down the text into sections that are somewhat independent. It incorporates the ideas of highlights, note taking, spaced repetition, self-questioning and recall; all the while you are not rushing to finish reading the content, you read to internalize as much of the knowledge as you can get.

Most textbook products are not like Erudite or Mindstone, they focus on the distribution of the digital artefact in an affordable and all-inclusive way, rather than the job that needs to be done by the student. They are not selling the ‘learning from textbook’ experience, they exquisitely replicate the analogue at a discount, with increasingly better affordances. Yet, to deliver a product or a tool that will increase the quantity and quality of learning from textbooks will require a redefinition of the problem and a step away from the delivery of text to the delivery of a guide to learning.