A light introduction to research data management

Demystifying the terms

Research data

Although a contested term, research data represents almost everything and everything that is raw and could be analysed for research. Can be (not exhaustive) text, numbers, images, tables, databases, corpora, etc. You will most likely hear arts and some humanities claiming they don’t produce data in their research, but the argument is that even a recording of their process, from inspiration to output constitutes data. The outputs from one research project could become the data of another researcher. A selected number of pages from a corpus, or an aggregated list of sources can also be data. In the social sciences, research data could be: all the raw interview files and transcripts, the survey responses and the actual survey questions, the social media aggregated data, the corpora to be analyzed etc.

Research data management

RDM- normally refers to all the processes from the creation of research data to its stewardship to ensure the data retains value. Many universities, if not all, will appoint one person to support [all research staff] with the management of research data. This will be either a small part of someone’s role, or as many as a team of 5 or more supporting RDM. There is… some debate… as to which part of the university should be responsible for the management of research data: in some, the library has taken an active role, in others the research support department, and in others even IT infrastructure. What this sometimes means, is that even though all these different teams of people are championing for RDM, none are undertaking decision-making roles. The library may want to run RDM infrastructures, but they can only run trainings, because they may depend on the IT skillset to implement certain services. And IT may not feel these are at the top of the priority list, hence much delay with implementation. Moreover, there are no real incentives for researchers to take care of their data post-publication or post-grant-end-date. And a big discourse in this space is around culture change being the major reason for RDM’s slow uptake. Tools for RDM include DMP Online (a checklist for researchers that want to comply with institutional and funders data policies). DMP Online was originally developed by the Digital Curation Centre in the UK, and is now a joint partnership with California Digital Library. There are a number of other checklists and tools that support offices can use to ensure compliance with RDM policies, such as the DMA dashboard. To find out more about research data management, the Jisc RDM toolkit is a good start as it is the most recent and links back to a variety of other links and resources.

Preservation

Refers to the processes of safeguarding digital data in order to make it accessible and readable even when the file formats or software used to open these files are obsolete. So for example, if you did some interviews back in the 1990s, and saved all the responses on the old 1995 Microsoft word file format, you will probably be unable to open these files now. A good preservation system would ‘read’ the file, identify the format, extract all metadata (file specs), check for a variety of errors and save the original 1995 word file, along with a copy which would continuously be updated to the newest file format, so that you can open and read the contents of that file. There are a variety of file formats, and some research projects use very specific software and produce unique formats that are harder to preserve. In these cases, preservation software will automatically convert the copy of the original file into a ‘common’ format (most of the time an open format). For instance, image files will be converted to JPEG2000 (open format) or TIFF (proprietary). Even though proprietary formats can be more robust, they carry more risk for the long-term (company goes bust, nobody will run any updates, hence become obsolete). You may be wondering, who decides how and when preservation software converts the files etc. There are a host of preservation experts that work together to produce standards and rules for different file formats. The National Archives in the UK run PRONOM - which is a file format registry where anyone can submit new file formats and requirements for their preservation. The Library of Congress in the US also runs a couple of initiatives to identify file formats and guide around their long-term sustainability. Most important thing to know: OAIS - the reference model/standard that contains all the recommendations for how to implement a preservation process. Examples of preservation software infrastructure: preservica, archivematica. To find out more about digital preservation, the Digital Preservation Coalition’s handbook would be a good start.

Archiving

Refers to the process of placing data that is no longer needed into long-term storage, most often offline and in a different location. Archived data is not easily accessible and would require manual retrieval. Unlike preservation, archived data remains unchanged over the years, in the original file formats. The most common software that universities use for archiving is Arkivum. Where RDM has been well-implemented, institutions will combine an archival and preservation system to ensure long-term sustainability and accessibility of the content. And potentially a repository interface, where the researcher will be uploading the data. Curation - the difference between data management and curation is quite subtle. Data management refers to the stewardship of data throughout its lifecycle, whereas curation deals more with the selection of data that will have a value in the future, making it accessible to other communities of researchers and ensuring its long-term preservation. When people refer to data curation, they refer to higher-level data challenges like: there is too much data and we don’t know which one to preserve; if you ask a researcher they will always say theirs is the most important data; how do we decide how many years should it be curated for; is it 10 years after last access or 10 years from creation…

Repository

A repository (within the research data management context) is a software that enables individuals and institutions to ’save’ data. You will have heard of figshare and zenodo, these are probably the most popular and loved repositories by researchers. However, there are more than 2k research data repositories worldwide (registry). Most of them are based or built upon these software: dryad (funded by NSF), eprints (funded by EPSRC), DSpace, dataverse, Fedora, samvera etc. Very rarely, if ever, repositories perform any preservation or archiving. A repository simply allows the researcher to save a copy of the data, s/he can choose to make it private or publicly available and most of the repository software can produce a DOI (digital object identifier). Universities may choose to have a repository for publications and one for data, or a combined data and publications repository, but most often just a publications repository. Since RDM is not yet a top 10 priority, most university policies will encourage researchers to publish their data in their disciplinary or funder repository, and only when they cannot find an appropriate disciplinary or funder repository among the 2k+ available worldwide, should they request institution’s help. Institutional repository are quite handy when it comes to the REF or any other type of reporting, because research support staff can easily pull the stats from their repositories around volume and impact of research. However, institutional repositories are still quite patchy and require a lot of manual involvement. Worth noting that many (about 30 to my knowledge from 2017) universities in the UK and South Africa have been subscribing to the institutional offer of figshare (researchers love figshare). The Wellcome Trust data repository also runs on figshare.

IR

IR refers to institutional repository and can be both for publications and/or data.

Open research data

Refers to the global initiative to make data accessible and reusable. You will hear many refer to the FAIR principles in relation to open data. FAIR stands for findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable. The principles were developed in 2014 by FORCE11, a network of researchers, librarians, archivists, etc that has grown organically. There are a dozen of metrics underpinning these principles that can be used to evaluate the level of FAIRness of data. Another important development in this space was the Horizon2020 Open Data Pilot, which allowed grant applicants to volunteer to make their data open. The next EC funding program will require all grant applicants to open their data. In the UK, most funders under UKRI require data to be open. If it wasn’t for BREXIT, there may have been more progress in this space, as the ex-former Universities minister set up a task force to review the open research data infrastructures in the UK and recommend policies and the way forward. In Europe, there has also been a few reviews of data infrastructures, for example this is the latest or an older quite well-known report on research infrastructures in the digital humanities

Metadata

Refers to the set of fields that describe a dataset, including but not limited to: title, year, authors, description, discipline etc. There are a few standards (minimum required fields that are enough to describe a dataset and ensure it can be understood and reused by someone else without contacting the author): Dublin Core, datacite schema are probably the most used. Figshare for example built its selection of fields based on the datacite schema. Some metadata standards are disciplinary, for example the most used in the social science is the data documentation initiative. Normally, repositories will allow the users to enter the metadata manually. There are some initiatives and enhancements of certain repository software to enable automated pick up of some fields. In a preservation system, however, a lot of the metadata, especially the one related to the provenance of the file, its format and technical specs will be automatically detected by the software. Identifiers - numerical and textual sequences for data (DOI), funders (FundRef), institutions and researchers (ORCID).

Challenges and barriers to curating data

In no particular order:

- language and terminology is not well understood policies across funders, institutions and publishers around data are weak and quite vague (open data doesn’t mean it has to be always accessible, could also mean send me an email and i will forward it)

- there is no way to check whether data practices are well implemented to enable more and better data sharing, researchers need to go through some serious ‘cultural changes’; researchers claim time to clean up the data and no attribution as major challenges; also many believe they will lose future publications

- data is quite patchy and metadata is not good enough to enable reusability of data infrastructure is poor, although a host of services exist to support different parts of data management and curation, most are not interoperable, meaning that people waste time uploading data multiple times into different services

- a variety of training programmes available, but skills are lacking among researchers and little interest or time to pursue this

- person-identifiable data poses big risks for open data

- tracking costs of managing research data: researchers don’t include them in grants to remain competitive (game theory); research support don’t always have a separate budget; many services are acquired across departments and there is not central budget to cost against for RDM activities; making it all hard to quantify the spending for the management of research data (and hence the risk of losing it)

WHY RDM is important

- Critically, to minimize data loss; it can be catastrophically bad: check out library burns

- one of the aspects that can impact research efficiency, integrity and dealing with reproducibility crisis

- it’s great for building reputation and reuse of your data, wider dissemination and impact

- potentially new relationship and collaborations if data is shared

Research data services

Note: these are used within universities mostly.

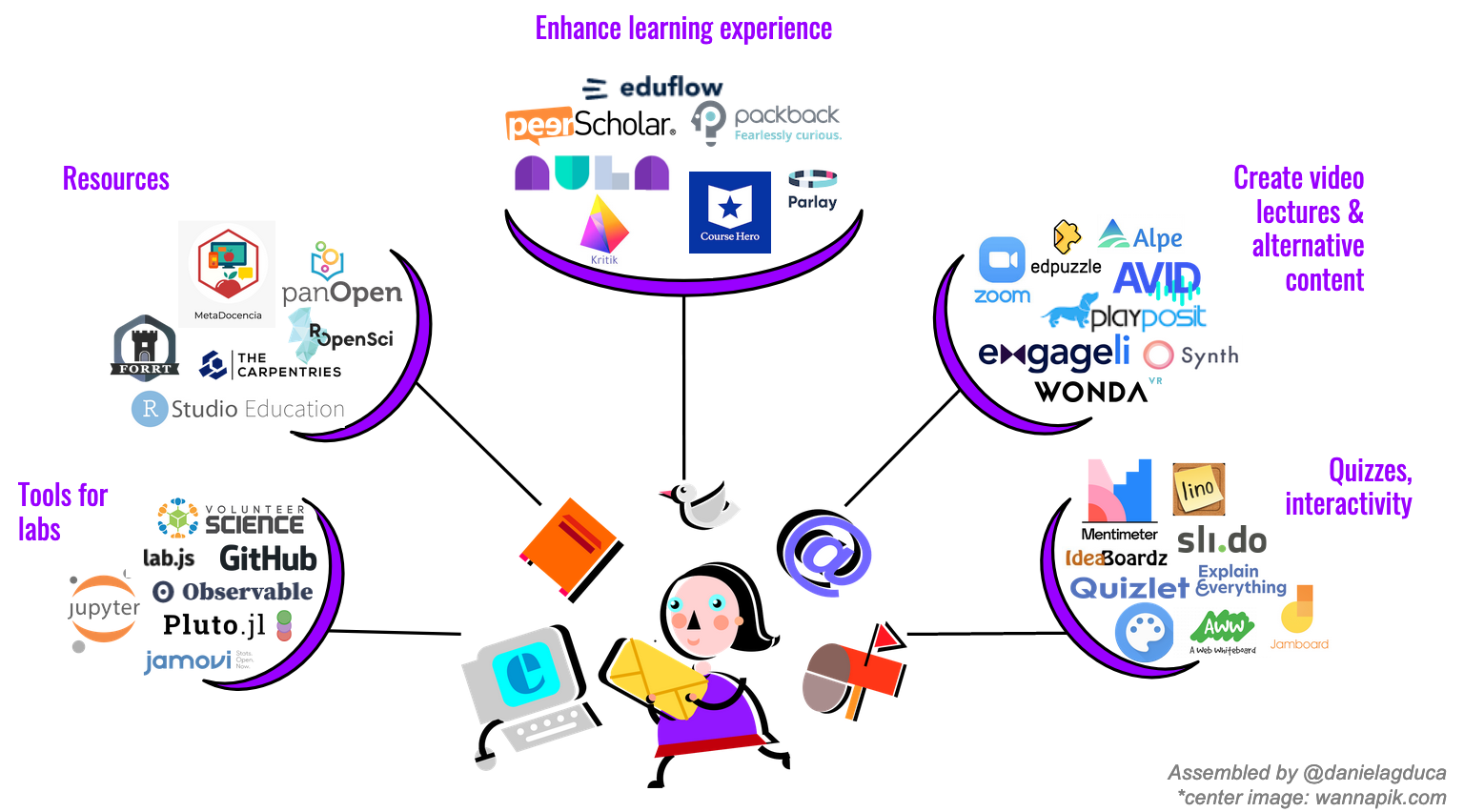

A good research data service will have a few components (imho):

- Training

- Researcher depositing data

- Research support preserving and archiving data

- And all would be interoperable and linked to publications and projects seamlessly

A number of universities are trying to provide parts of this service, many established research data support roles or even teams. The first step all universities take is to define their research data policy. Commonly, this policy recommends that the responsibility for the curation of data lies with the researcher. But we’ve seen some changes recently, whereby institutions and national structures are trying to support this piece.

In the UK, there is an expectation for RD services to be part of the national infrastructure: Jisc massive research data shared service project, 18 pilot institutions in the UK.

In the Netherlands, DANS offers the following core services as part of the national infrastructure, but not for free:

- DataverseNL for short-term data management

- EASY for long-term archiving

- NARCIS, the Netherlands’ national portal for research information.

In the US, most RD services are provided by individual institutions.

A couple of years ago, I looked at a variety of software and tried to posit which ones would make for a good and as comprehensive as possible research data service, here are a few combinations I had come up with (though this is not an exhaustive list):

DANS - DataVerse and EASY recently partnered with Dryad Strengths: tried and tested, repository+archiving Weaknesses: NL/EU focused, not clear how much preservation they do, may be expensive

Ex-Libris Esploro: pilots: University of Iowa, Lancaster University, University of Miami, University of Oklahoma, University of Sheffield Strengths: 2 universities in the UK including Lancaster, UCL has Ex-Libris Primo, end-to-end research service Weaknesses: as of 2018, it was work in progress

Figshare with partner* Strengths: analytics, user experience, user support, storage bundles, large files, researchers like Figshare Weaknesses: will have link or expect faculty to upload twice to fighare and preservation, very few examples for repo+preservation

Mendeley Data (Elsevier) with partner* Strengths: integrated with Pure, may be developing a preservation system?? Weaknesses: may not be able to work with Ex-Libris (competitors) or Symplectic Elements

*Best partner: preservica Strengths: can be on premises and use UCL local storage, admin analytics Weaknesses: expensive, training costs extra, not very user friendly

Events, reports, and other indicators of growing interest in this area:

- 2003: NIH expects the data from $500k funded projects to be accessible and open

- 2005: NSF expects researchers to share their data and other raw materials, including software

- 2011: Research funders in the UK developed common principles on data policy

- 2012: Royal Society published its ‘Science as an open enterprise’ report championing policies around open data, one of the most cited reports underpinning the move towards open science in the UK

- 2013: G8 Open Data Charter and Technical Annex promotes sharing data

- 2013: Research Data Alliance, a global network of research data experts (now close to 5k), was launched as a bottom up approach to develop research data infrastructure

- 2014: PLOS open data policy, a lot of pushback

- 2014: first draft of FAIR data principles at FORCE 11 workshop, these were set in stone and launched later in 2016

- 2016: a number of UK’s leading research organisations developed and signed the Concordat on Open Research Data built on 10 principles

- 2016: IRUSdata UK, metrics for data usage, COUNTER compliant

- 2017: European Open Science Cloud (still a bit of a mess) will potentially integrate data services along other research infrastructures and build interoperability

- 2018: UK Open Research Data Taskforce recommendations for building infrastructure: Realising the potential launched to public Feb 2019

- research data discovery initiatives in Australia and the UK, these are aggregations of institutional repositories to enable search across them.

Organizations that are quite visible in the RDM and open data space

National: Jisc, DANS, ANDS, NIH, NSF, The National Archives, NEH

Libraries: British Library, California Digital Library, Library of Congress

Others: CNI, DataCite, Open Knowledge Foundation, Digital Preservation Coalition, Digital Curation Centre, UC3, Force11

Leading Universities: Edinburgh University, Universities of California